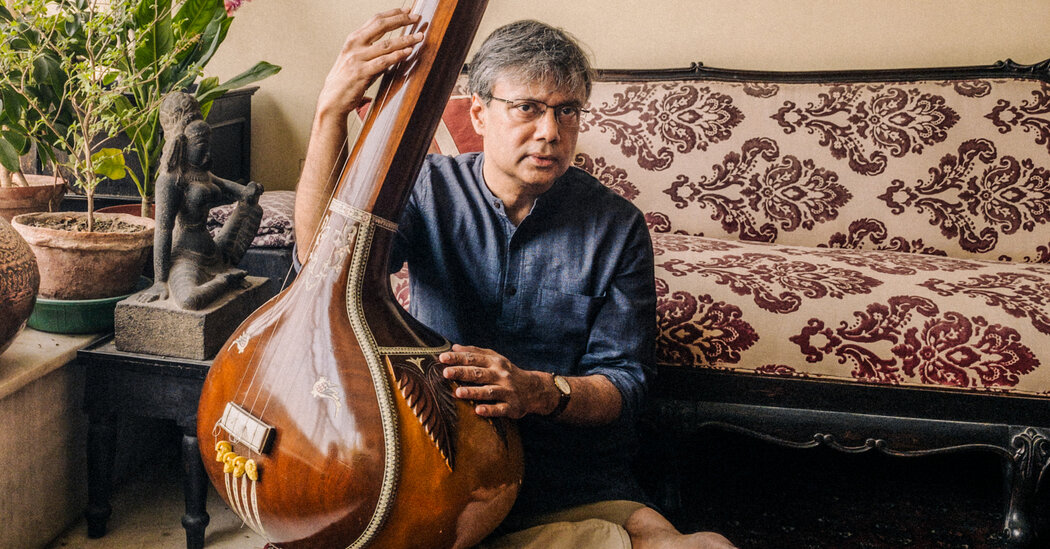

Amit Chaudhuri, a writer and singer, combines memoir and musical appreciation in Finding the Raga: An Improvisation of Indian Music, which is now available on the New York Review Books. In it, Chaudhuri records a personal journey that began with a western-oriented love of the singer-songwriter tradition, followed by a headless immersion into Indian classical music.

This legacy remained overwhelming for him until an accident that he describes as “deafness” drew his attention to the elements that ragas and Western sounds have in common – a finding that led to his ongoing recording and performance project “This Is Not Fusion ”.

In the book, Chaudhuri reflects on the raga, the framework of Indian classical music. Resisting the urge to find an analogue to Western tradition, he writes: “A raga is not a mode. That is, it is not a linear movement. It is a simultaneity of notes, a constellation. “Elsewhere he adds that it is neither a melody, nor a composition, nor a scale, nor the sum total of its notes. In an interview, Chaudhuri gave a brief introduction to the raga and described the development of his musical life from childhood to “This Is Not Fusion”. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

One of the first musical experiences I had was with my mother singing Tagore songs. I grew up in Bombay and remember the calm energy of their style. it wasn’t sentimental, but it was alive. Without realizing it, I was drawn deeply into the sensual immediacy of tone and tempo, and also into a precise style whose emotion lies more in the tone than in the added feeling.

Of course there was also “The Sound of Music” and “My Fair Lady”. I was in love with Julie Andrews for a while. Then when I was 7 or 8 years old my father bought a HiFi turntable that came with some free records that I probably played a role in choosing without being informed in any way. I think one of them was from the Who, which I liked a lot; “I Can See for Miles” was one of my favorite songs. I also had a thing for the early Bee Gees and of course the Beatles.

I started playing guitar when I was 12 and when I was 16 I composed songs in a kind of singer-songwriter form. At the same time I became interested in Hindustani classical music for the first time.

There were several reasons. I had a youthful attraction to difficulty and was more interested in complex tonalities. I listened to Joni Mitchell, and I loved that she could be melodic and open in her harmonic compositions, while being quite complex at the same time. I also knew people like Ravi Shankar, partly because of the Beatles. When we thought of Indian classical music, we basically thought of instrumental music: tabla players playing really exciting rhythmic patterns, getting applause at the end of their improvisational spells, and of course the sitar and sarod. Vocal music seemed a little out of the way, arcane.

But then I heard Vishmadev Chatterjee – what an amazing voice. And at that time there was also this man, Govind Prasad Jaipurwale, who started teaching Hindi devotions to my mother. I realized that while teaching he was doing tiny improvisations with his voice that indicated a different kind of imagination and training. I began to be receptive to the kind of Indian classical music that had always existed but that I had excluded. I asked my mother if I could learn classical music.

For some time different types of music lived side by side. I played a little bit of rock guitar. And I was working on an album that I thought was my way of being a singer-songwriter. My song “Shame” comes from this time. Its melody begins with the note of C sharp, then the word “shame” returns to C sharp in the chorus. It goes to that note after touching C – so chromatic notes are introduced at the end of the chorus with some degree of alienation since the chords are C major and A major. I think I’ve already reacted here to the way notes in North Indian classical music create a hypnotic effect through small shifts.

Then I started practicing a lot of Indian classical music, about four and a half hours a day. And I spent a lot of time listening to music, understanding what happened to the time cycles, and then singing and improvising. Obviously, that took over some of the other musical activities.

I should say that a raga is not a melody. It is not a note, a scale, or a composition – although the raga is sung as part of a composition. However, you can identify the raga by a specific arrangement of notes related to the way they ascend and descend. A certain pattern on the ascent and a certain pattern on the descent characterize the raga.

You can’t introduce notes that aren’t in the raga, but you can slow them down. You can escape the immediate display of the demarcation. Part of this workaround is imagination and creativity. You could climb up to the octave and then you would be done with a series of notes that could be sung in a song in a minute. But doing this for 30, maybe even 40 minutes – that becomes an expansive idea of creation that not only outlines or indicates, but finds different ways of speaking. That is what is at work here, especially in the khayal form.

The extended time cycle allows you to explore these notes to make the ascent and descent very slow. The ear may recognize the fast version of the ectal rhythm system, which sounds like the normal version.

When this additional space occurs, you are not maintaining time in the ordinary sense, but you are aware that the 12 beats of the ektaal have been multiplied by four beats each until they end and you are returning to the beginning.

So there is still so much time left to sing and talk about the progress. That is an extraordinary modernist development. You can hear it in Raga Darbari by Ustad Amir Khan. It’s an amazing shot.

Ragas are basically found material. Indians might say there are eighty-three of them, or a thousand; I dont know. In the North Indian classical tradition, no more than 50 ragas are sung today. And maybe there are 30 that you hear over and over again, considering that we don’t hear the ragas in the morning and afternoon because there are concerts in the evenings.

This is because ragas have specific times and seasons. The Raga Shree is associated with twilight and evening.

And the Raga Basant, which has almost the same notes, is sung in the spring.

If architecture is a language with which one can understand space and time, so is raga. It’s like language too. For example, you don’t use the word evening to refer to the morning. Likewise, one does not sing the morning raga Bhairav in the evening. However, with recordings, if you wish, you can listen to ragas at any time of the day. Until the recording studios hit, ragas only came to life for a short time.

So that was mainly the music that I was practicing. The singer-songwriter had finally retired. But by the late nineties the zeal of the convert who had obsessed me in my youth was gone, and I began to return to my record collection and listen to Jimi Hendrix. Curved notes, the blues, the Gujri Todi raga – it all came together as I listened. A moment of “misheard” occurred when I thought I heard the riff from “Layla” in that raga.

It happened again a week or two later. I was standing in a hotel lobby and someone was playing this Kashmiri instrument and suddenly it seemed to start in “Auld Lang Syne”. Of course it wasn’t. But then I thought: is it possible to create a musical vocabulary – not about consciously bringing things together, East and West, but about the kind of instability of who I am and the richness of what I had discovered in that moment? capture. And that’s why I call it “no fusion”.

“Summertime” happened around the time I was creating these pieces. In it I improvise on the Raga Malkauns, but in the form of “Summertime”, an early type of jazz composition based on the blues. I show that it is possible to improvise on Malkauns according to this form, as a jazz pianist does. But I’m bringing in a different tradition.

The same thing happens in “Norwegian Wood”. I take the raga bageshri and improvise in the space that each piece gives me. “I once had a girl, or should I say she once had me” – that gives me space to improvise on these notes. What I do is a characteristic of Khayal. So I would say again, it’s not a fusion, because fusion artists don’t. What they do is they sing their own stuff in a western setting.

Research into these ideas has been profoundly gratifying. Has my musical journey closed? I didn’t become a singer-songwriter again, but I put everything I know together. When you are a creative artist, the things you know come back to you in some way. I am very happy that this happened to me.