While Congress has debated aid to state and local governments for the past few weeks, some states have announced surprising news: Their finances are no longer looking quite as bad as they feared in the uncertain early days of the pandemic.

The states are still largely suffering from the economic crisis. But California now expects a one-time slump this fiscal year. Wisconsin said it might still be able to throw away some revenue in its rainy day fund. Maryland increased its forecast earnings for the second time this fall. And Minnesota is now forecasting a surplus.

This good news partly reflects poor economic expectations from six months ago; Even modest numbers look good now, compared to the worst fears written on national budgets this spring. And state officials say they will continue to need federal help as they expect the effects of the pandemic to drag on for years and hit local governments. After all, federal aid is part of what has spurred it on so far.

The states with rosier outlooks are also complicating Washington’s state aid political battle, which is likely to be pushed into the New Year after lawmakers dropped aid from a year-end stimulus agreement that is nearing completion. Republicans have called state aid a bailout for lavish blue states. But many states that look better now are among the most advanced tax structures in the country, and that’s part of what saved them this year.

This recession, unlike many before, has amassed its worst effects on low-wage workers. This means that national budgets, which depend most on wealthier residents to fund government, have not been so badly damaged by an economic crisis that left the wealthy largely unscathed.

“We have a recession for low-wage workers and we just have a strange situation for everyone else,” said Peter Franchot, the controller for Maryland, who last week saw an estimated revenue increase of $ 64 million for that fiscal year compared to September announced estimates (which are up $ 1.4 billion from May).

Forecasters and state officials said they didn’t see this in May and June when they drafted budgets envisioning a severe downturn that might more closely resemble the great recession – with widespread layoffs among manufacturing workers, with one collapsing Stock market and economic development The pain spread into employee offices and civic subdivisions.

In typical recessions in which unemployment rises sharply, government revenues also fall sharply. But the relationship between the two was much weaker this year. In fact, the inequality associated with the Covid recession has protected many states from worse fiscal ramifications.

But that doesn’t mean that everything is okay.

“Despite the progressive tax structure, despite the wealth we have in Maryland, despite the fact that we are back in a safe haven of tax revenue, the suffering is just totally unacceptable,” said Franchot, who has called Maryland to be next to that Congress to set its own incentive.

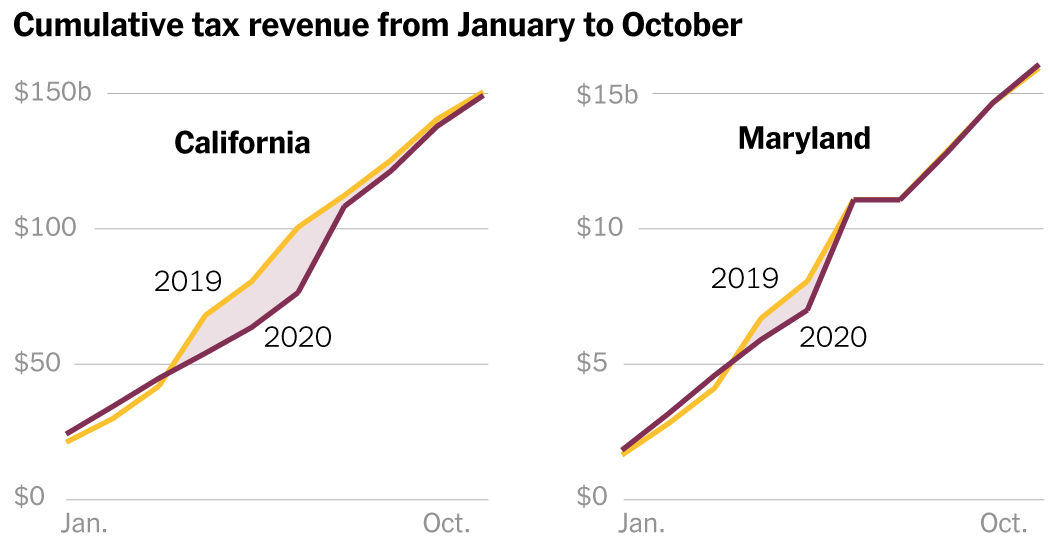

In California, where there is a progressive income tax, the state revenue generated through October this year was only marginally lower than the same period in 2019. Texas, which has no state income tax and is considered one of the least equitable tax systems in the country, has been in a more precarious position.

While Texas doesn’t rely on taxes from its volatile energy sector to fund its base budget, decreased oil and gas production and lower prices have also contributed to the decline in overall tax revenues.

Florida and Nevada, which are heavily dependent on tourism (which was hurt by the pandemic), also have no income tax. And Florida is one of the few states that never attempted to levy sales tax on online transactions following a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that expanded that power to states. (In Texas, the ability to tax e-commerce was a huge challenge at the moment, as it added about $ 1.3 billion last year.)

Since the pandemic began in March through October, tax revenues in 38 states have declined 5 percent or less year-on-year, according to the Urban Institute. When states made far more serious projections in the spring, they failed to fall back on previous experience and tried to be conservative in their estimates, said Lucy Dadayan, a senior research fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

“To be fair, they didn’t have any information,” Ms. Dadayan said. “Yes, the revenues are higher than the original projections made in the spring immediately after the pandemic. But that doesn’t mean that earnings are doing well. “

In all of these states, federal incentives have played an important role. It’s not that the crisis was excessive; The fact is that federal aid really worked.

Stimulus checks and additional unemployment benefits increased the consumption of laid-off workers, which in turn supported sales tax revenues. Most states also levy income tax on unemployment benefits. And all that federal support eased the burden on states of providing a safety net for families in trouble, even as federal dollars helped cover many of the state’s Covid expenses.

States that rely on higher income taxpayers have been helped by other unexpected disparities in this recession. Consumption has shifted from services that are difficult to consume in person during a pandemic to goods that are much more taxed (for example, you pay taxes when you buy a lawnmower but usually don’t pay taxes when you pay someone who mows your lawn).

In California, forecasters in March never expected the stock market to rise as much as it has before. This has increased capital gains, which are taxed in the state as regular income. And a number of lucrative IPOs – another unexpected trend in the midst of the recession – have also contributed to government revenues.

From August through October, California’s personal income, sales, and corporate tax revenue increased 9 percent over the same window last year, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office. That shows how well the wealthy fared this year. The resulting budget damage is also due to the fact that the state planned a budget for bad times in June.

“This is really a temporary situation,” said Gabriel Petek, “ the state legislative analyst who prepared the latest budget outlook. The budget effects of this downturn have been pushed into the coming years when the state expects deficits that could further burden the services.

“It turns out a bit that the state is doing fine financially, and it’s true that our sales picture is better than we thought,” said Petek. “But the only reason we’re in a better budget position is because of this one-off difference between what we collect this year and what we have accepted in the budget that we would collect.”

Like other states, California still doesn’t know how bad the winter flood of the pandemic will be. In the near future, states will no longer be able to fall back on one-off pots such as rainy day money. When the public health emergency ends, the federal government will cut additional payments to states to cover Medicaid. And local governments will continue to have problems as they rely on even less stable sources of income such as parking fees, public transport charges and hotel taxes.

States are still facing both sides of the inequality of the pandemic – the wealthy residents who have been stuck, bought stocks and new cars, but also the low-wage workers who are struggling.

“Even states with lots of rich people often have lots of low-income people,” said Tracy Gordon, senior fellow of the Tax Policy Center. State and local governments will ultimately be responsible for the safety net, she added, “and they are not built to absorb that risk.”