Rappers have an obvious advantage over side-born poets when it comes to rhythm. But also poets can shape the rhythm through stress patterns as well as through their lines on the page. Poets differ from prose writers in that they, not the typographer, choose where their lines should end, thus giving them the opportunity to play with a reader’s sense of time. Enjambment, when a syntactic unit overflows from one line to the next, is a fundamental poetic practice that empowers poets with the ability to create and re-shape meaning. In “Highest” from his upcoming “Somebody Else Sold the World” collection, 49-year-old Indianapolis poet Adrian Matejka rifles over Travis Scott’s 2019 hit “Highest in the Room,” but where Scott’s lines almost completely end – that is , dissolved in a complete phrase – Matejkas are mostly enjamged. Sometimes the effect is a syncopation: “This is / Machu Picchu high.” In other cases a picture is paused and then revived with a parable: “I raise / like the highest black hand in history class.” Still other times, Matejka enables a complex idea to unfold over several lines: “I rose like that Blood pressure of someone / black reproduced in the textbook / this monochromatic year. ”Matejka’s line breaks attest to a year of pandemic and racist violence and deny any effort to overcome the pain.

Moments like these show the reciprocity between rap and poetry, little formal things that have a big impact on meaning. “For me, it’s sound,” says 45-year-old Los Angeles-based poet Khadijah Queen of her work’s connection to hip-hop, although her poems also make use of silence. In her latest collection “Anodyne” (2020) she uses the entire page and writes not only with words but also with the space around it. Their lines dance, yes, but they also trip, cancel, pause, and begin in a way that’s reminiscent of an inventive MC playing a dozen different beats in a row.

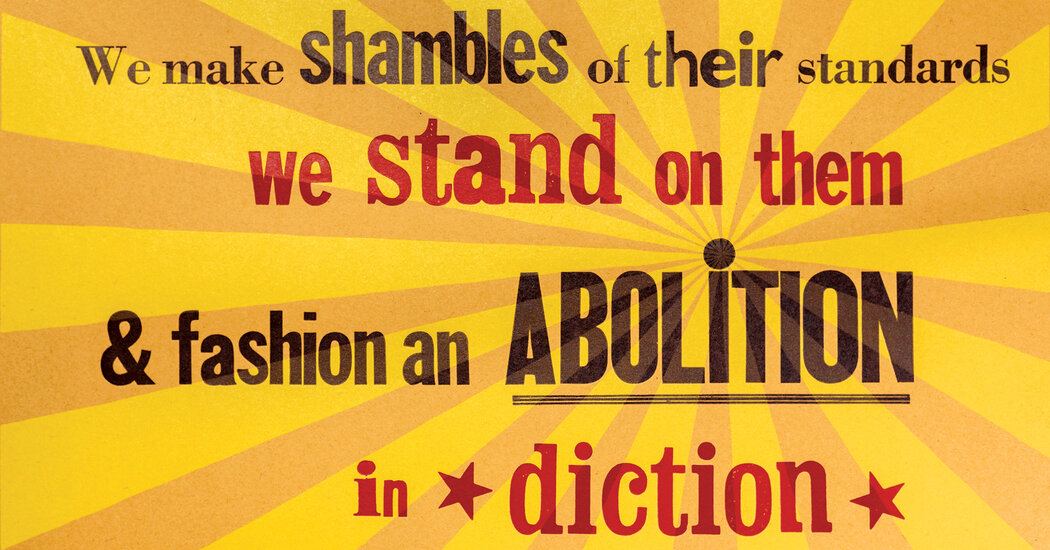

Queen also understands her role, and that of her fellow poets and rappers, as necessarily engaged in civic work. She looks at Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, perhaps the most prominent black writer of the 19th century, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery and the rights of women and children on her platform. “Our job is to grasp what people feel in this time of contradiction: the difficulty and the beauty together. We are called to clearly recognize what is happening, ”says Queen. After the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and many others, rappers were also moved to express themselves through songs. Atlanta’s Lil Baby, 26 and one of the most successful emerging artists, released The Bigger Picture in June, in which he seriously deals with police brutality: “It doesn’t make sense; I’m only here to vent “In the past year, several other songs have expressed the anger and pain of Americans: Terrace Martin’s“ Pig Feet ”starring Denzel Curry, Daylyt, G Perico and Kamasi Washington; Noname’s “Song 33”; Meek Mills “Otherside of America”; YOUR “I can’t breathe”; Anderson .Paak’s “Lockdown”. For Queen and other black poets, hip-hop is not just beats and rhymes, but something more necessary as well. Hearing black voices speaking on their own terms creates refuge, especially at a time when blackness and blacks are besieged. “I love hip-hop because it emphasizes the use of black language as the standard,” she says. “It’s a space to be who you are without apologizing.”