When the music starts we start dancing. It’s the beginning of April and for the first time in 13 months I’m rehearsing with a partner in the New York ballet studios. Ashley Bouder and I meet while we are dancing side by side. After more than a year of dancing alone, we are not used to this kind of closeness.

We’re working on the first moments of George Balanchine’s “Duo Concertant” to record music on my iPhone while our repertoire director Zooms walks in with her adorable daughter bouncing on her lap. Ashley and I have been tested for Covid twice and we both wear masks. It’s a far cry from work as we know it, but we’re back in studios that we know, dancing steps we’ve danced for years, and we’re holding hands.

The excerpt we are preparing for a film by Sofia Coppola for the company’s virtual spring gala takes just 2 minutes and 11 seconds. But this is the longest time I’ve danced with anyone else in a long time, and after doing it on that first rehearsal, I got upset.

With every breath I take, I suck my mask to my mouth, which makes it even harder to recover. “I smile!” Says Ashley and makes sure the repertoire manager Glenn Keenan and I know that she’s happily dancing behind her mask again. I giggle breathlessly. I’m glad we’re back too, but disappointed with how impersonal it is to dance in a mask. I expected going back to this work would be emotional and precious, but with the short snippet of the snippet we’re dancing and the fact of our masks, it feels strange, almost like we’re dancing side by side, but not together.

After the outbreak of the pandemic last year, my life and that of my colleagues, like everyone else, have radically changed. We were used to gathering in sweaty groups in windowless rooms, where we kept hugging and touching each other for choreographic and emotional reasons. Last year we danced alone in small studios that we made ourselves.

Using my portable dance mat, I took ballet lessons from the five New York apartments I’ve lived in since March. out of my sister’s garage, driveway, and deck in Maine; and from my parents’ living room in Philadelphia. In the fall, I was allowed to return to the City Ballet studios in Lincoln Center to dance alone. More recently, I’ve danced with small groups of masked colleagues in our studios to keep my distance and mostly to stick to ballet exercises. But with the exception of an idyllic bubble residence in Martha’s Vineyard with 18 other dancers in October, it’s been some time since I’ve actually danced with my colleagues.

In a way, that time outside of the studio and the stage felt necessary. Groups of us in the company meet regularly for Slack and Zoom to develop strategies on how we can strengthen and transform our community in order to prepare for a hopefully changed cultural landscape. And I had time to properly rehabilitate my ankle, which I injured in the fall of 2019, and think about what is most valuable to me about my job and my dancing.

During this break, I have often longed for the space (and the strength) to do a coupé-jeté manége, or longingly thought of the fulfilling exhaustion that overwhelms me when the curtain falls on a particularly challenging ballet. But when I really imagine that I can dance again, two moments always come to mind. The first comes in the opening section of Justin Peck’s “Rodeo”. Dancers perform in a number of small groups and hurry to take the stage for short, playful vignettes of each other. When it is my turn, I run at full speed towards the center and pull myself in front, a few meters away from two other dancers. There is a pause in the music where we all turn a blind eye. A smile creeps into our faces as the music introduces us to our dance.

The second moment is in Jerome Robbins’ Grand Waltz “Dances at a Gathering”. Really, I just think of a dancer’s face. I picture Indiana Woodward who sometimes reminds me of my younger sister and grins at me. We go on stage with a pony flanked by four other dancers, and she smiles so hard I think she might burst with excitement and explode into something unstoppable.

These moments of connection are only possible in the context of a dance. My colleagues and I find this unspoken recognition of each other and our shared passion in the intimacy and physical closeness of a danced world on stage. And it is these relationships and closeness that have been established on stage and in motion that have been impossible on our video screens and in our socially distant dancing.

In ballet we are told where to stand, what to do, and how often to do it. However, this doesn’t change how the connection makes sense when I reach for my partner’s hand – when I offer my hand as I was taught and it is taken as my partner was told. The prescribed nature of ballet takes none of the intimacy I experience over and over again in these repeated gestures and choreographies. Intimacy is heightened by familiarity, but also by the fact that my partner and I are cutting out our own space in these dances at the same time.

The everyday act of taking a partner’s hand before dancing a combination of steps that requires trust and spontaneity can feel like essential recognition of our personal investment in each other and in the work we share. This type of physical contact has been a comfort to me for a long time, and before the pandemic was so often my way of showing care.

“Duo Concertant”, which Ashley and I have danced together again and again since 2015, is full of these moments and rewards her choreographic ingenuity and humanity. Balanchine made “Duo” for the Stravinsky Festival in 1972 – a week-long homage to the composer who had been Balanchine’s long-time friend and favorite collaborator. Their connection and Balanchine’s devotion and closeness to Stravinsky are evident in “Duo”. It’s a closed job. Intimate, a natural ballet from the Covid era.

Dancing this ballet means living in a world that you have created yourself. There are only four performers on stage: two dancers and two musicians. The two pairs of performers challenge and complement each other, the music expands the dance and vice versa. In a concertante there is often the pairing and counterpoint of two musical lines: tension and duality. In “Duo” the piano and violin play opposite each other and together in a conversation that crosses the dramatic and lively terrain of the piece.

This score resulted from further close cooperation. Stravinsky composed it to play on tour with the violinist Samuel Dushkin and adapted it to Dushkin’s hands, to his abilities. And apparently Dushkin weighed in too – his riffs for Stravinsky’s composition and arrangements were worked into the last piece.

Many pairings, many intimacies are built into this music, this work: Balanchine and Stravinsky, Stravinsky and Dushkin, the violin and the piano, the music and the dance and of course the two dancers. The ballet feels like a joke and like there is nothing else my partner and I could possibly do to this music together on stage.

When the curtain opens on “Duo Concertant”, Ashley and I stand behind the piano and look at the pianist and the violinist. We stand and listen for the first four minutes of the dance. After this charged opening, I take Ashley’s hand and we go to the other side of the stage and start dancing. Only now, after we’ve listened, are we ready to dance. Only now, after listening, is the audience ready to see.

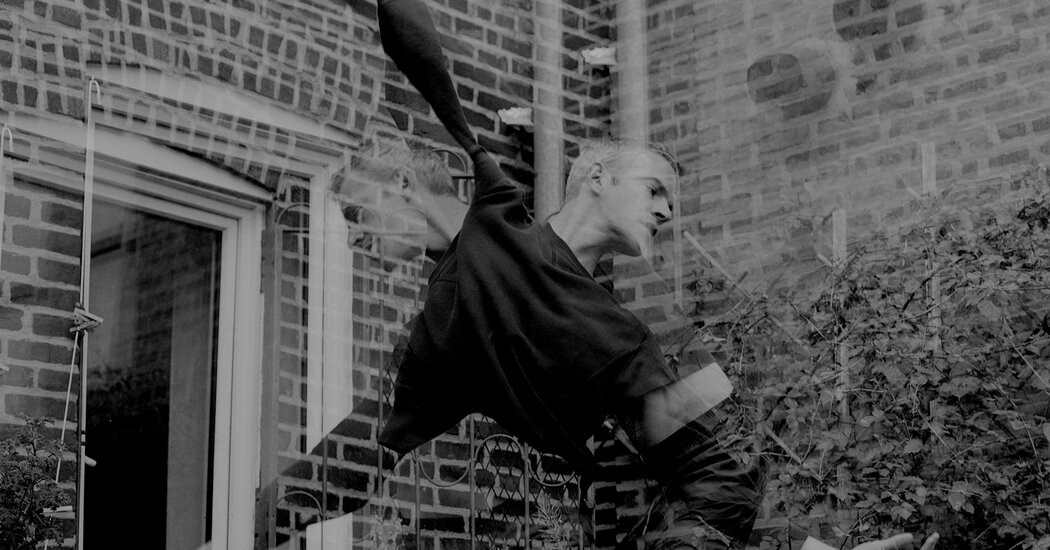

The violinist intones six somewhat wistful notes, then the piano begins a rhythmic stroll and Ashley and I move up and down – I’m up when she’s down. “Like a metronome,” says Glenn. Then we add in our arms like we’re trying things out, like we’re building something, like we’re building ourselves up to something. We jumble at imaginary sounds, play for each other, then she does a series of poses and I tap my arm in a circle like a clock and count to the dance that frees us from that measured, constant clip.

What follows is a dance of pushing and pulling, forwards and backwards, from side to side. We stamp and do it and fling our legs and arms in quick, casual leaps and lunges. We annoy each other and forward and just before the movement ends we pause, catch our eyes, I offer my elbow and we rush to the musicians just in time to hear them play the final notes.

The dance continues on stage – but this is where Ashley and I will stop filming. Manageable, if a bit teasing. As we prepare for the day of shooting and our time in the studio progresses, our dancing feels more and more like the dancing that I missed. Our breathing is soon no longer so desperate, our body relaxes, we find the rhythm again to try new things, to be in a studio together.

On Friday we are in costume for a dress rehearsal before filming on Tuesday. Our section is turned left behind the stage – almost on stage, but not entirely; We’re back to work, but not quite. Ashley and I piled on the warm-ups unused to the thin leotards and tights we wore every night – costumes meant to be exposed and naked. There are people watching – Sofia Coppola and her team, and a handful of familiar and reassuring faces from the City Ballet’s artistic and administrative staff. It’s a fraction of a fraction of the audience we’re used to, but more eyes than a year before. Ashley and I are both nervous.

“All right!” someone calls. “Let’s see.”

We take off our costumes and take our place. After a few false starts with the recording, it starts. I can feel our dancing pulse with a little more than what we gave at rehearsals. Ashley’s body is tense with exertion and excitement, and our movements have a kind of swing and power that is lacking in our time in the studio. We wear masks, we are backstage and the audience is small, but as the dance unfolds Ashley and I find something for us in this shared experience.

“That was fun!” Says Ashley, putting her hand lightly on my shoulder when we’re done. “I could tell you were smiling.”

Russell Janzen is a dancer with the New York City Ballet.