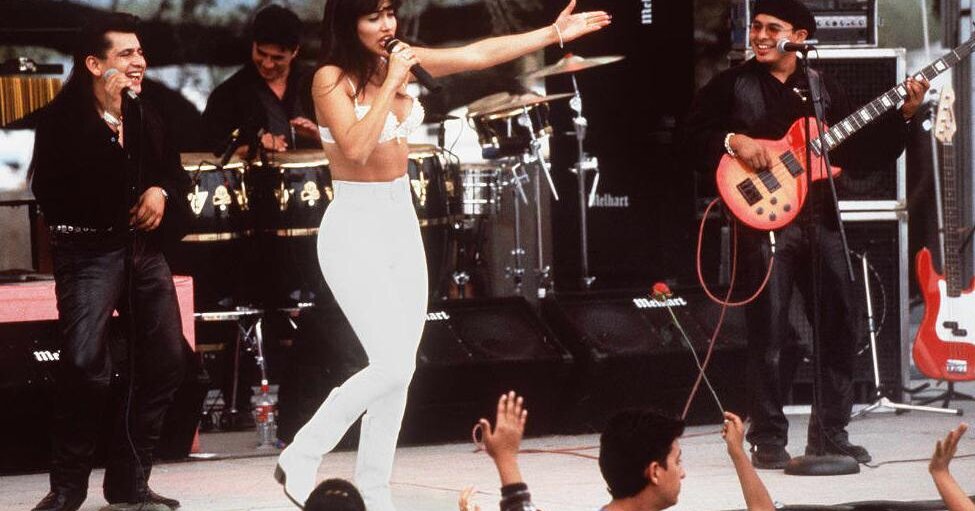

First there was Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, the pioneering Latina singer who inspired a generation of artists and was killed on the cusp of national fame. Then there was Selena, the movie that polished her legend and brought another Latina artist to fame.

Tribute albums, a Netflix series, and podcasts followed, and now, more than two decades after the film was released in 1997, a group of lawmakers are pushing for “Selena” to be listed on the national film register, declaring that his Taking up pressure on Hollywood could increase Latino representation in the ranks of the industry. The legislature’s efforts have been welcomed by film and Latino study experts, who said it was long overdue.

“It’s a recognition of Chicana and Latina talent in acting and representation,” said Theresa Delgadillo, professor of Chicana and Latina studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, “and a music innovator at the center.”

Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez broke into the male-dominated Tejano music industry in Texas, winning critical admiration, large following, and then a Grammy in 1994. A year later, only 23, she was shot dead by the founder of her fan club. Her English-language debut “Dreaming of You” was released posthumously.

For over a quarter of a century after her death, Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez remains a pop culture icon, especially among Mexicans and Latinos from her native Texas. At Spotify, she has more than five million listeners a month. “This month the Grammys will honor her with a special merit award.

But the 1997 film with Jennifer Lopez as Selena and Edward James Olmos as her Father, deserves credit too, said Representative Joaquin Castro, a Texas Democrat who leads the effort in Congress. In an interview, he said that Latino creators and their stories are too often pushed aside by gatekeepers of American culture like Hollywood and the national register, and that Latinos in all media are too often portrayed by negative stereotypes such as gang members, drug dealers, and hypersexualized women.

“Hollywood is still the picture-defining institution in the United States,” Castro said of his project for a more balanced representation. “All of us walking around with brown skin or a Spanish surname have to face the stereotypes and narratives created by American media, and historically some of the worst stereotypes have come out of Hollywood.”

In a letter from the 38 members of the Hispanic Caucus in Congress, Castro wrote that “the exclusion of Latinos from the film industry” “reflected the way Latinos continue to be excluded from America’s full promise – a problem that is yet to be resolved when our stories can be fully told. “

He said the National Film Registry could “help break down this exclusion by preserving important cultural and artistic examples of American Latino heritage”.

Each year a committee selects 25 films to be included in the national register established by Congress in 1988. Of the 800 films in the register, at least 17 are examples of Latino stories, including “El Norte”, “The Devil Never” Sleep “ and “Real women have curves,” said Brett Zongker, a spokesman for the Library of Congress. From 11 Latino directors on the list, 9 are men and two are women.

Although the film register tries to reflect the diversity in America, Zongker said, “Unfortunately, women and people with color are underrepresented in film history, especially as directors.”

The gap between Americans and the main cast extends to speaking roles. Although Latinos are the largest minority group in the United States, making up 18.5 percent of the population, a 2019 study found found that only 4.5 percent of all speaking characters in 1,200 highest-grossing films from 2007 to 2018 were Latino.

Mr Castro said he is still collecting entries on other films to submit, but “Selena” as a particularly loved film is the focus of efforts. Frederick Luis Aldama, a Latino film and television professor at Ohio State University, said the film “shows the complexity, dignity, humanity, and wealth of a Latino father and daughter, and it really shows us that we are not just the ‘bad hombres, as the twitter feeds have told the world over the past few years. “

Whether the film register accepts it or not, a wave of appreciation for the work of Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez has gripped the entertainment industry.

“They have these kind of artists that we lost when they flourished,” said Daniel Chavez, professor of Latin American studies at the University of New Hampshire. “These young characters become mythical in a way.”

In addition to the upcoming Grammy, Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez was recognized in the National Recording Registry last year for her 1990 album “Ven Conmigo”. The Netflix show “Selena: The Series” premiered last year and will return in May. And a podcast about her legacy titled “Anything for Selena” released its first episodes last week.

The podcast host Maria Elena Garcia said that as a young girl struggling with her identity, she was inspired by how Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez took on her Mexican and American heritage without apology.

“She was whole in both places,” Ms. Garcia said in an interview. “Although she didn’t sound like Mexican-born people, she told them it was, and I can say, my heritage. It was incredibly profound to me, even though I was a little girl. “

When Ms. Garcia saw her success, she added on the podcast and felt like “she brought us with her”.

It was this sense of representation for young Latinas that drove filmmaker Gregory Nava to direct Selena, he said. While pondering whether to make the film in the mid-1990s, Mr. Nava remembered a walk in Los Angeles and saw two young Mexican girls wearing Selena t-shirts. “Why do you love Selena?” he asked her.

“Because she looks like us,” they said.

“Our stories need to be told,” said Mr Nava in an interview. “These young girls that I made ‘Selena’ for are all grown up and have young girls and they need nicer pictures of who we are.”

Some scenes from “Selena” have proven to be big for many Latinos, like one in which Mrs. Quintanilla-Pérez and her father Abraham Quintanilla talks about the problems Mexicans face when they simply speak English and Spanish for different audiences.

“Being Mexican-American is tough,” says Mr. Olmos as Mr. Quintanilla. “Anglos jump over you if you don’t speak perfect English. Mexicans jump over you if you don’t speak Spanish perfectly. We have to be twice as perfect as everyone else. “

In the end, Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez became an idol for many Mexicans and Americans alike, but the effect of the film is probably felt most strongly in Texas, the singer’s homeland. “Selena” was made on a small budget, said Mr. Nava. When trying to re-enact Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez’s last appearance at the Houston Astrodome, he reached out to the ward for help.

“I insisted we shoot in Texas because I wanted to shoot in their country,” said Mr. Nava. “She was the earth, sky and sun of Texas.”

In newspaper advertisements, he asked the community to dress as if they were going to the opening concert of Ms. Quintanilla-Pérez’s concert. Mr. Nava said more than 35,000 people showed up.

And droves came out for other scenes, including an additional one who was later elected to Congress, Mr. Castro.