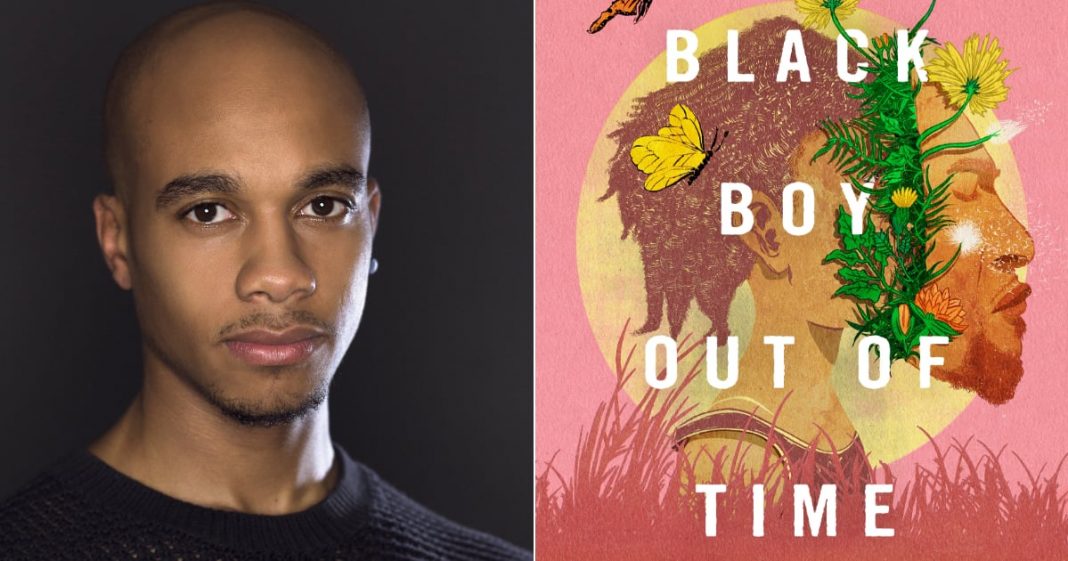

Black boy from the time is the debut memoir by Hari Ziyad, who is among other things editor-in-chief of Racebaitr, Lambda Literary Fellow 2021 and prolific essayist. In a word, it’s exquisite.

At the heart of the memoir is the concept of abolition, which, according to Critical Resistance, refers to “a political vision aimed at eliminating detention, policing and surveillance, and creating permanent alternatives to punishment and incarceration”. In practice it looks like living together in an actual community: a real hug of our perceived other beyond institutions that would put people in cages and out of the public eye rather than social problems like homelessness, inadequate health care and unemployment to tackle. as trumped by the abolitionist icon Angela Davis. According to Ziyad, “It all comes back to the work we do to become free.”

Ziyad writes with a clarity and strength that surpasses any recent memories, and interweaves writing about abolition and carcinoma with a rousing series of letters to her younger self as part of her inner-child work. One of 19 children in a mixed family, Ziyad was born to a Hindu Hare Krishna mother and a Muslim father in Cleveland, OH. They are black, strange, and – like too many racial children are made – grew up painfully fast. But in her memoir, Ziyad dials back the clock and turns inward. As they peel off the fetters, they reveal to the black child and adult a plethora of truths about the need for blacks’ liberation, and when given the grace to grow freely they become variable.

Carcinogenic logic is so widespread that the work of abolition goes beyond dismantling prisons and wards that wreak havoc and penetrate deep into the psyche, which becomes a place of reproductive logic of carcinogenic until we consciously unlearn it.

Ziyad patiently reveals how harmful cancer is for black people and how intrinsically punitive thinking can be, how we understand our outer and even inner life. Carcinogenic logic is so widespread that the work of abolition goes beyond dismantling prisons and wards that wreak havoc and penetrate deep into the psyche, which becomes a place of reproductive logic of carcinogenic until we consciously unlearn it. Liberation is therefore as much inner work as outer work. Like a social archaeologist, Ziyad tries to discover his true self – the inner child – who lives beneath binary thinking and what shape it as misafropedia, or “the anti-black contempt for children and childhood experienced by black youth” . They encounter places of trauma and get away with nuances and new meanings by taking care of their inner child with the care of a loving parent. “I would like to offer colonized blacks – and especially myself – a kind of road map to win back those childhoods we sacrificed,” writes Ziyad, “or which were given up for us because of misafropedia.”

The joy of Black boy from the time is in the unconditional love it exudes for all blacks and how it cares for black children’s experiences. It is in its utter surrender to freer, more daring black futures; in his mind. It lies in the calm and wisdom of its author who is the kind of cultural critic and black liberation advocate that our political moment yearns for. Hailed by Darnell L. Moore as “the black-loving art that is both shotgun and balm”, Black boy from the time is just great, to the point that the best this reviewer can do is ask you to read it and know for yourself.

In February, I sat down one on one with Ziyad – then one on one plus a live studio audience (via Google Hangouts) as part of a speaker series at Group Nine Media – to talk about it Black boy from the time and the healing work of abolition in action.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.