In a small clinical trial, an experimental Alzheimer’s drug slowed the rate at which patients lost the ability to think and care for themselves, drug maker Eli Lilly announced on Monday.

The results have not been published in any form and have not been fully reviewed by other researchers. If exactly, it will be the first time a positive result has been found in a so-called phase 2 study, said Dr. Lon S. Schneider, Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Gerontology at the University of Southern California.

Other experimental drugs for Alzheimer’s disease were never tested in phase 2 studies, went straight to larger phase 3 studies, or did not produce positive results. The Phase 3 trials themselves repeatedly had disappointing results.

The two-year study included 272 patients with brain scans that suggest Alzheimer’s disease. Her symptoms ranged from mild to moderate.

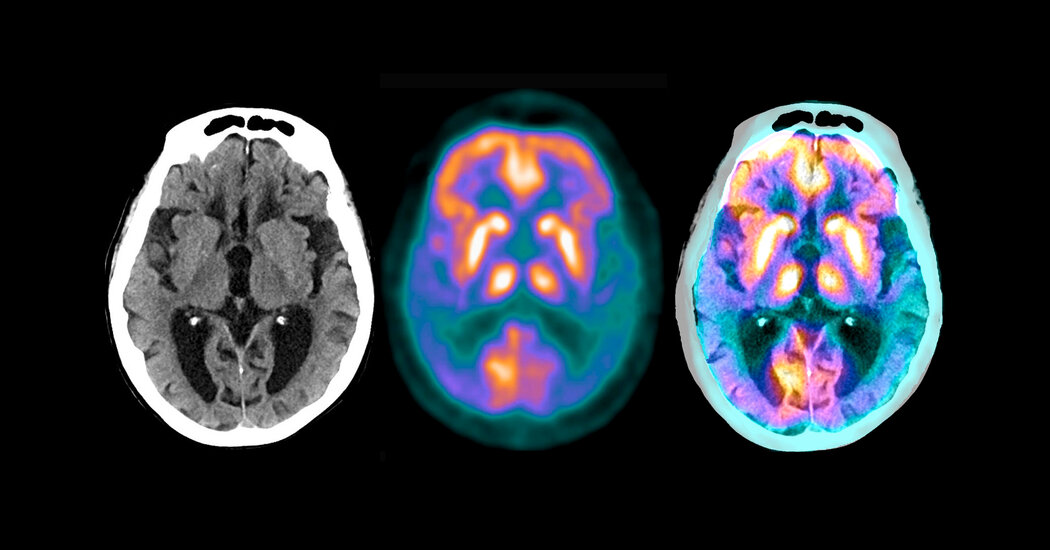

The drug donanemab, a monoclonal antibody, attaches to a small portion of the hard plaques in the brain, which are made up of a protein, amyloid, that is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. The patients received the drug by infusion every four weeks.

Participants who received the drug had a 32 percent slowdown in the rate of decline compared to those who received a placebo. In six to twelve months, plaques were gone and stayed gone, said Dr. Daniel Skovronsky, scientific director of the company. At this point, the patients were no longer receiving any medication for the duration of the study – they were given a placebo instead.

The small study needs to be replicated, noted Dr. Michael Weiner, a leading Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of California at San Francisco. Even so, “this is big news,” he said. “This gives hope to patients and their families.”

Eli Lilly has not released the relevant data needed for a thorough analysis, said Dr. Cutter. For example, the company only provided percentages describing functional decline among participants, not the actual numbers.

The company will provide this data at a subsequent meeting and in an article in a medical journal, said Dr. Skovronsky. Eli Lilly received the results on Friday and had to report them immediately, he said, as the results may affect Lilly’s stock.

Dr. Schneider, who served on an independent data protection and monitoring body for the study, said he was not allowed to disclose more data than the company provided.

The experiment served as a test for the so-called amyloid hypothesis. The idea is that Alzheimer’s is closely related to amyloid buildup in the brain; If amyloid accumulation can be prevented or reversed, the disease can be prevented or cured.

Drug companies have spent billions of dollars testing anti-amyloid drugs to no avail, leading many experts to believe the hypothesis is wrong – or that the only way to treat Alzheimer’s is to start very early, before clinical ones There are signs of illness.

The Eli Lilly study recruited patients who were not based on symptoms but rather on scans that showed significant buildups of amyloid in their brain. The researchers also looked at a protein, tau, that forms spaghetti-like tangles in the brain after the disease begins.

“We needed mild to moderate entanglement pathology, but not so many entanglements that the disease may no longer be hoped for,” said Dr. Skovronsky.

The primary endpoint or aim of the study was a measurement that combined performance on mental reasoning and memory tests with ratings of participants’ performance in activities of daily living such as dressing and meal preparation.

The main side effect has been seen regularly in patients given experimental monoclonal antibodies to treat Alzheimer’s disease: an accumulation of fluid in the brain. It occurred in nearly 30 percent of patients, said Dr. Skovronsky, but most of them had no symptoms. The effect was seen on brain scans.

During the study, Eli Lilly started a second phase 2 study, Trailblazer 2, in the hope that the initial efforts would produce results. These results are expected in 2023.

Dr. Skovronsky said Eli Lilly will speak to the Food and Drug Administration and regulators in other countries about giving patients access to the drug.

“Sure, the dates are exciting,” he said. “But we have to see what the regulators say.”

For 25 years he has hoped for definitive evidence that the amyloid hypothesis is correct.

“This is what we’ve been waiting for,” said Dr. Skovronsky.