The rolling can go on in an endless rotation for hours as the partners move in each other’s arms on a crowded dance floor. It requires considerable levels of physical contact, which is why the waltz was considered a guilty pleasure until the early 19th century when its popularity eventually plunged appropriateness. And now during the coronavirus pandemic, the close partner dance is raising its eyebrows again.

In Vienna, the home of the waltz, a wave of cancellations has ended the annual ball season. Hundreds of luxurious celebrations are usually held across the city in January and February, including a New Year’s Eve ball, the Hofburg Silvesterball, in the Imperial Palace. The lockdowns began shortly after this year’s events ended. Planning for a new season’s programs came to a halt.

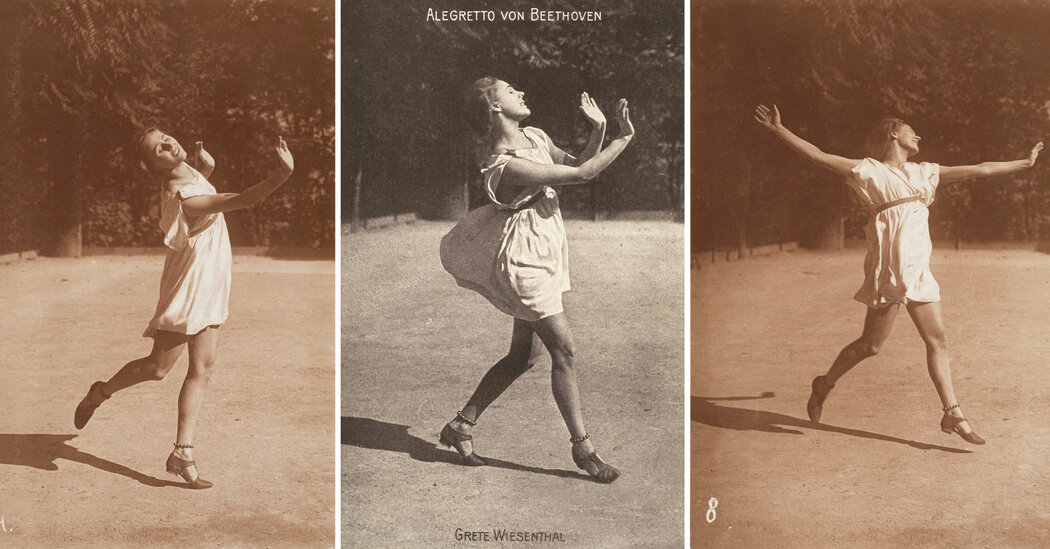

The waltz may have a reputation for being the ultimate partner ballroom dance – as it is traditionally performed at the balls – but there is another interpretation that resonates in this pandemic year of physical distancing. More than a century ago, the Viennese dancer Grete Wiesenthal transformed the waltz into a powerful form of solo movement.

When Wiesenthal first performed her choreography with its swirling, euphoric movement and the floating arches of the body, she became an advocate of free dance in Vienna and a cultural force in the city’s highest artistic circles.

Although her name is not usually found among internationally known pioneers of modern dance such as Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Loie Fuller, Wiesenthal is revered in Austria, where her dances have been regularly revived since her death 50 years ago.

Like many Viennese, Wiesenthal, born in 1885, grew up playing the waltz, but trained in classical ballet. She refined her technique at the Vienna Court Opera School, where she later insisted that the emphasis was not on art.

A solo waltz style was Wiesenthal’s answer to what she saw as the debilitating relationship between ballet and music. She saw the art form and the productions of opera as hopelessly committed to uniformity, with no room for the dancers to present themselves.

Wiesenthal developed her own technique, which she called spherical dance, which concentrated on a different axis than ballet. Twists and extensions were placed on a horizontal line of the body, and her arms, torso, and legs would extend across the room at the same time. With bent knees, she manipulated the curve of her curves and was able to lean into sickle-shaped back bends. She was not tied to a partner and was able to gracefully sweep her arms to plunge them into a balance that defies balance.

The spinning was a critical movement in their dances, just like in the waltz. And while their contemporaries Duncan and St. Denis also spun more freely and openly than ballet, for the most part they remained vertical. Wiesenthal’s torso was not pinned in a stacked position over her hips so she could create more exaggerated angles.

Wiesenthal was also inspired by nature. Aside from smaller theaters, she often performed outdoors to remove the barrier between the audience and the stage, and created dances that reflected the elements and their surroundings.

The cultural historian Alys X. George, author of “The Naked Truth: Viennese Modernism and the Body” (2020), said in an interview that the artistic avant-garde in Vienna, who adored Duncan and St. Denis, was enthusiastic about the local Wiesenthal, when she introduced her contemporary style.

“That was just electrifying for the city because Wiesenthal really embraced this Austrian dance form, the waltz, and breathed a new life into it,” she said. “She freed it from the balls, she took it outside, she also connected it to nature, but kept the connections to music that so invigorated Viennese culture.”

The Viennese have loved the waltz for centuries. It began as a wild, popular country dance in parts of Germany and Austria in the 18th century and quickly spread through the social classes and became known among the upper classes and the aristocracy as an elegant form of entertainment. In Vienna, the waltz – the city’s version is characterized by the three-stage structure of the music, which was danced at high speed – supplanted the tight minuet in the early 19th century, and composers such as Johann Strauss senior and Joseph Lanner made it famous worldwide.

In the waltz Wiesenthal found what, in her opinion, ballet had become cold – musicality. “Nobody knew anything about the merging of music and movement,” she said in a lecture from 1910. “My desire for a different dance, for a truer dance became stronger and clearer and at the same time I learned how not to do ballet dances should do. “

Despite her disenchantment with ballet, she began her professional career at the Vienna Court Opera. There she danced for several years and left after a controversial casting decision, which put her at the center of a fight between the then opera director Gustav Mahler and the ballet master Josef Hassreiter. Mahler gave Wiesenthal – a member of the Corps de Ballet – a solo in “La Muette de Portici”, which made Hassreiter angry and directly violated his wishes.

Just a few months after the premiere of “La Muette”, Wiesenthal left the company and, as she put it, a life in which one “stayed in step and didn’t get out of line”.

At the beginning of 1908 Wiesenthal and her sisters Elsa and Berta made their debut in the Cabaret Fledermaus with original choreography. They danced and played solos together, but it was Wiesenthal’s “Donauwalzer” solo to Strauss’s “On the Beautiful Blue Danube” that was the highlight of the program. (When she became famous, street musicians sang her along with Strauss’ waltzes, the dancer La Meri said decades later.)

The Wiesenthal sisters danced in Vienna and Berlin and performed in the London Hippodrome in 1909. They were a hit in London, where The Dancing Times later wrote that the sisters “weren’t mere actresses; They were poems. “When Wiesenthal came to the US alone for the first time in 1912 and brought her program to winter theater, she called The New York Review, a weekly theater newspaper,“ the high priestess of joy and ecstasy ”.

Wiesenthal’s energetic approach to dance inspired many collaborations with Vienna’s leading artists. In 1910, the playwright and librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal became a close creative partner with her growing reputation as a soloist. She starred in his pantomimes and silent films, distilling complex narratives through their emotional essence rather than literal gestures.

She was also seen in the world premiere of Richard Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s “Ariadne Auf Naxos” (1912) in a self-choreographed role and was commissioned to perform Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in the spring of 1913, the same month that the curtain for “The Ritus des Spring. “Although it never came about, said Andrea Amort, founder and director of the dance archive at the Music and Art University of the City of Vienna, it should be a new production, with a libretto by Hofmannsthal and danced by Nijinsky, Wiesenthal and Ida Rubinstein.

Throughout her career, critics and audiences admired her dance for its gentleness, and critics consistently noted her charm and femininity in her reviews. But Wiesenthal experimented with the extremes of the expressive potential of the waltz.

She also explored a deeper connection between the dancer and the audience. “It seems to be her secret that her dancers do not wallow with each other, but alone, so that the audience feels like partners,” said dance author George Jackson in the program notes for George Balanchine’s “Vienna Waltzes”. (1977). (Balanchine’s work also features a solo waltz in its final section, moving across the stage, luring the audience with it.) Wiesenthal, wrote Mr. Jackson, “could take the closed waltz and open it for inspection without destroying beings . “

Her choreography is full of subtle nuances, and her subtleties delighted audiences when she performed in intimate theaters. However, their dances lose some of their vigor when performed on a large opera stage. Jolantha Seyfried, a former first soloist of the Vienna State Opera Ballet, who performed three Wiesenthal works in the 1980s and 1990s, remembered rehearsing her “Death and the Maiden”.

“In addition to these large swings and floating movements, she has very small, very sensitive movements,” said Ms. Seyfried in a video interview and demonstrated an energy that flows through her own hand. “Sometimes she only works with her fingers, she lets her fingers breathe.”

Ms. Seyfried is currently working with Ms. Amort (both are professors in the dance department of the Music and Art University) to revive a wider exploration of her technique, not just her repertoire. The Ballet Academy of the Vienna State Opera is now also considering including its technique and choreography in its curriculum.

Wiesenthal’s articulation of the music and her choice of composers – Strauss (Johann, Josef and Richard), Schubert, Beethoven, Chopin – were inextricably linked with the waltz. But it was a completely new vision.

When she returned to America on her second tour in 1933 with the dancer from the Vienna State Opera Willy Franzl, the audience had turned to various forms of expressive modern dance and her style was received as pure nostalgia. The New York Times dance critic, John Martin, wrote: “Your dance was exhilarating in its day, make no mistake. When seen at a later date in relation to its time, it will dance intoxicatingly again. “

Maybe now is that future time. It is a year in which a bold solo waltz that is not tied to any major theater conventions can not only be refreshing, but also exhilarating again.