When asked when the trial would end, Indiana Republican Senator Mike Braun remarked, “I think we’re just a prisoner of time here.”

Mr. Merlino and a small group of colleagues started a fast, modulated pace and started the reading marathon at 3:21 p.m. (For comparison: the sixth book in the Harry Potter series is 652 pages.)

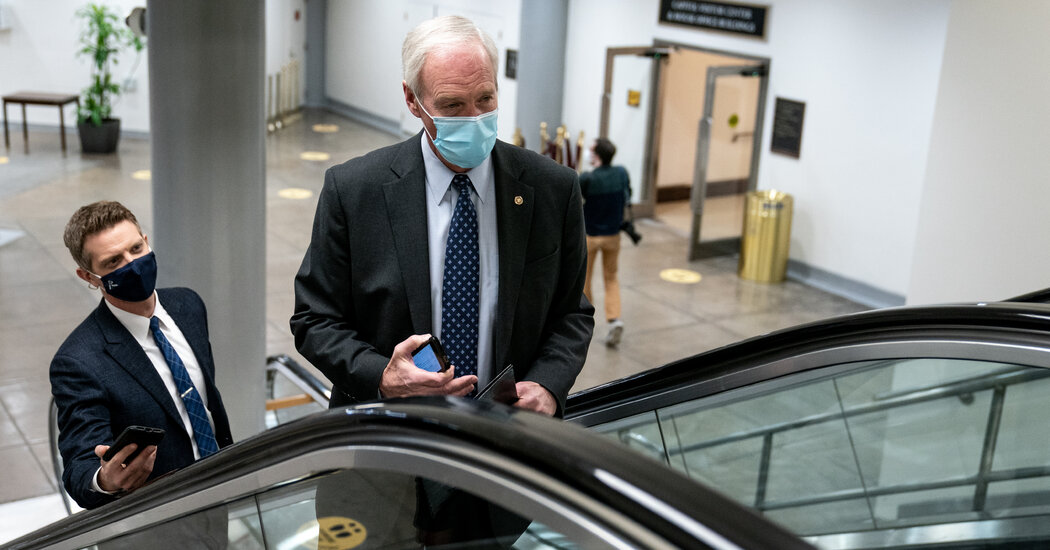

Sometimes they would walk across the podium with a small lectern and recite the text in a largely empty chamber. You spoke to a busy carousel of stenographers, ground staff, the Chamber presiding Democrat, and Mr. Johnson, who had to stay on the ground – or find a like-minded Republican to spell him to keep Democrats from stopping the process and keep going.

At 7:21 p.m. the group had reached Page 219.

It was unclear what precedent there was, according to the Senate Historian’s Office, for reading such a large bill, since the Congressional report does not tell how much time is spent reading bills.

The Senate has provided funding to employ at least one employee since 1789. Nearly a dozen people now share responsibility for recording Senate minutes, reading laws, calling the list, and other procedural duties.

“The positions are setbacks from pre-Xerox machines and the immediate availability of hard copies or now digital copies of laws,” said Paul Hays, who was a reader in-house for nearly two decades in the 1990s. “You have to try to find a balance between the sound of a robot and that of a lawyer.”

After reading everything from the impeachment ruling on former President Bill Clinton to a lengthy presidential message from former President Ronald Reagan that lasted about 35 minutes, Mr Hays acknowledged that a clear reading may not help complete understanding.