A New Year is underway and theaters across the United States will remain closed. Vaccines are finally being distributed, but the virus is still spreading. Given this uncertain situation, many dance artists and dance hosts seem to be on hold – done with the 2020 makeshift projects but unsure of what, if anything, to try next.

That could be responsible for the tentative feel of this year’s La MaMa Moves! Dance festival. The year scheduled for May has been canceled, but some of the artists have been invited to contribute to a virtual replacement, rotating programs and artist discussions that will be streamed on the La MaMa website on Tuesday and Wednesday, and January 26th and 27th. Solos, short videos and works in progress create a picture of the moment: Not much that is finished or substantial, but with promising flashes all around.

Kevin Augustine’s “Body Concert” is the work-in-progress camp. The Artistic Director of the Lone Wolf Tribe, Augustine, is an experienced puppeteer and puppet maker. His most recent project includes foam rubber body parts – hands, legs, eyes, all skinless like anatomical models without flesh – which he manipulates in a black body suit and face mask. Instead of presenting this project in video form, he gives us a kind of “making of” advertisement for it.

Many of the performance fragments are unsettling. It is both delicate and disturbing to watch fingers attached to a skinned arm palpate a skinned leg, especially when the exposed bones touch like a compressed forehead. But the conversation behind the scenes and unnecessary reminders of how difficult the current circumstances are keep suppressing the illusion. It’s a 30 minute teaser.

Anabella Lenzu’s “The Night You Stopped Acting”, similarly discursive, is disturbing in another way. Lenzu speaks directly to the camera and shares some favorite music and pieces of old dances performed in the present with footage of her younger self over her shoulder. She jokes about the virtual assistant Alexa who doesn’t understand her Argentine accent. It alludes to the dictatorship in Argentina and the story of the disappearance of the people. What dominates, however, is her self-satisfied person, who breaks out in wiggling eyebrows and crazy grins. The video appears to be mistakenly the portrait of someone who can’t stop acting. Is that an answer to time or is it always like that?

The most dance-centered selection comes from the Norwegian choreographer Kari Hoaas. Instead of presenting a complete work, she has converted an earlier one, “Heat”, into several short solos, which she calls dance haikus. Individual shots in visually striking locations – a former Oslo airport that has been converted into now empty offices; a parking lot with a puddle that doubles as a reflecting pool – the films are each titled with a single word and are evidence of a haiku-like economy.

Or they almost do. The pieces consist mostly of slow, crumpled movements and usually end well: the dancer in “Grow”, framed on a staircase, finally descends from the frame as if in water; the dancer in “Lot”, who wriggles like on a wire rope on a flat floor and steps out with a proud strut. However, the essential effect of each piece is diluted or not strong enough to echo through reduction.

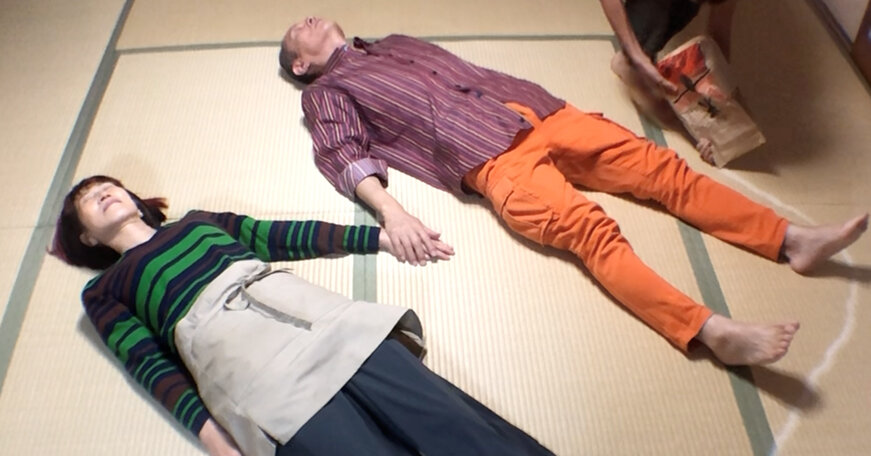

“The Yamanakas at Home” by Tamar Rogoff and Mei Yamanaka is another work that is presented without explanation. It’s a quiet, 10-minute film about a Japanese couple who are haunted by a character in camouflage suits. Although shots of this character on the stairs reminded me of the creepy bob in “Twin Peaks,” the ultimate impression is a kinder ghost that just seems to want to get down and dance.

This is a wish shared by the protagonist of Rogoff’s other contribution “Wonder About Merri”, a short film from 2019 that serves as the inspirational coda for the festival. Merri Milwe has dystonia, a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary convulsions. We learn this, useful to us, if implausible to her, when she looks up her condition in the dictionary.

At the end of the five-minute film, after Merri responded to music from a car by getting out of her wheelchair and dancing on the sidewalk, an episode the film treats as a miracle, she crosses out the definition and writes in a rejoinder : “Then why can I dance?”

Without further explanation, the question feels a little forced. Who said she can’t? But the implicit answer is one that not only dancers could hear. Just as a condition does not define a person, Merri seems to show it so that circumstances cannot completely limit a dancing mind.