Dozens of the best-known black business leaders in America are banding together to call on corporations to fight a wave of voting laws put forward by Republicans in at least 43 states. The campaign appears to be the first time that so many powerful black leaders have organized themselves to directly alert their colleagues that they are not advocating for racial justice.

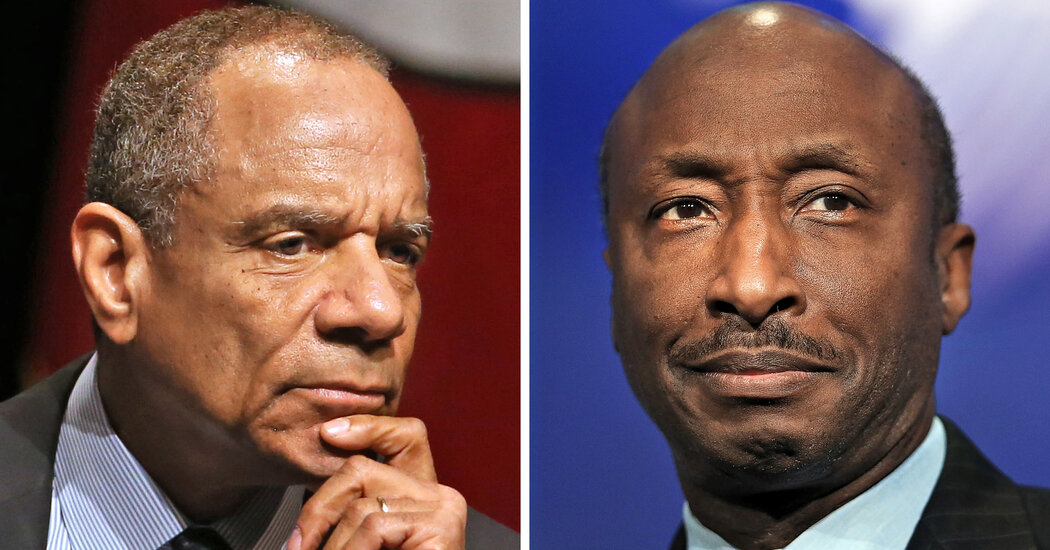

The effort, led by Kenneth Chenault, a former executive director of American Express, and Kenneth Frazier, executive director of Merck, are in response to the swift passage of a Georgian law that they claim will make it harder for blacks to vote. With the debate over the law raging for the past few weeks, most large corporations – including those headquartered in Atlanta – have not commented on the legislation.

“There is no middle ground here,” said Chenault. “You are either in favor of getting more people to vote or you want to suppress the vote.”

The executives did not criticize specific companies but called on all American companies to stand up publicly and directly against new laws that would restrict the rights of black voters and use their clout, money and lobbyists to open the debate with the To influence legislators.

“This affects all Americans, but we also need to recognize the history of voting rights for African Americans,” said Chenault. “And as African American executives in Corporate America, we wanted Corporate America to understand this and to work with us.”

The letter was signed by 72 black executives. These included Roger Ferguson Jr., the executive director of TIAA; Mellody Hobson and John Rogers Jr., the co-directors of Ariel Investments; Robert F. Smith, managing director of Vista Equity Partners; and Raymond McGuire, a former Citigroup executive who is running for Mayor of New York.

In the days leading up to the passing of the Georgian law, almost no large corporations spoke out against the legislation, which introduced stricter requirements for identifying voters for postal voting, limited drop boxes and an extension of the legislature’s power to vote.

Large Atlanta-based corporations, including Delta Air Lines, Coca-Cola, and Home Depot, made general statements of support for voting rights, but none took any particular stance on the bills. The same was true for most of the executives who signed the new letter, including Mr. Frazier and Mr. Chenault.

Mr Frazier said he only paid marginal attention to the matter before the Georgian law was passed on Thursday. “When the law was passed, I started paying attention,” he said.

When Mr. Frazier realized what was in the new law and that similar bills were being proposed in other states, he and Mr. Chenault decided to take action. On Sunday, they began emailing and texting a group of black executives to discuss what other companies could do.

“Nobody seems to be talking,” said Mr Frazier. “We thought if we spoke up it could lead to a situation where others felt a responsibility to speak up.”

In business today

Updated

March 30, 2021, 6:28 p.m. ET

Among the other executives who signed the letter were Ursula Burns, a former executive director of Xerox; Richard Parsons, former Citigroup Chairman and Managing Director of Time Warner; and Tony West, the chief legal officer at Uber. The leadership group, with support from the Black Economic Alliance, bought a full-page ad in Wednesday’s New York Times.

Executives hope that big companies will help keep dozens of similar bills from becoming law in other states.

“The Georgian legislature was the first,” said Frazier. “If the American company doesn’t get up, we’ll pass these laws in many places in this country.”

In 2017, Mr. Frazier became the first executive to publicly step down from President Donald J. Trump’s corporate advisory council after the president responded unequivocally to violence by white nationalists in Charlottesville, Virginia. His resignation caused other executives to distance themselves from Mr. Trump and the advisory groups disbanded.

“As African American business people, we don’t have the luxury of being spectators of injustice,” said Frazier. “We don’t have the luxury of being on the sidelines when injustices like this occur all around us.”

In recent years, companies have taken a stance on government legislation, often with great effect. In 2016 and 2017, when conservatives in states like Indiana, North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas rolled out so-called bathroom bills, large corporations threatened to relocate their business if the laws were passed. These invoices were never legally signed.

Last year, the human rights campaign began to convince companies to join a pledge in which they expressed their “clear opposition to harmful laws restricting LGBTQ people’s access to society”. Dozens of large companies, including AT&T, Facebook, Nike, and Pfizer, have signed up.

For Mr. Chenault, the contrast between the response of the business community to this problem and the electoral restrictions that disproportionately harm black voters was significant.

“They had 60 big companies – Amazon, Google, American Airlines – that joined the statement in which they clearly opposed harmful laws restricting LGBTQ people’s access to society,” he said. “So, you know, it’s bizarre that we don’t have companies that can stand up to this.”

“This is not new,” added Mr. Chenault. “When it comes to racing, there is a different treatment. That’s the reality. “

Activists are now calling for boycotts against Delta and Coca-Cola over their lukewarm engagement before Georgia passed the law. And there are signs that other companies and sports leagues are getting more into the issue.

The head of the Major League Baseball Players Association said he “looks forward to” a discussion of the All-Star Game’s move from Atlanta, where it is scheduled for July. And JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon released a statement Tuesday reiterating his company’s commitment to voting.

“Votes are fundamental to the health and future of our democracy,” he said. “We regularly encourage our employees to exercise their basic right to vote, and we oppose efforts that may prevent them from doing so.”

This language echoed the statements made by many large companies before the Georgian law was passed. The executives who signed the letter will likely seek more.

“People ask,” What can I do? “Said Mr. Chenault.” I’ll tell you what you can do. You can speak out publicly against discriminatory laws and any measures that restrict Americans’ eligibility. “