DAKAR, Senegal – For six days, parents held a vigil at the school in northwestern Nigeria, where their boys, more than 300 of them, were taken away by armed men at night.

The armed men’s attack on their town of Kankara was a painful replica of the kidnapping of 276 school girls in Chibok in 2014 by the Islamist extremist group Boko Haram of the Chibok girls were not registered years later.

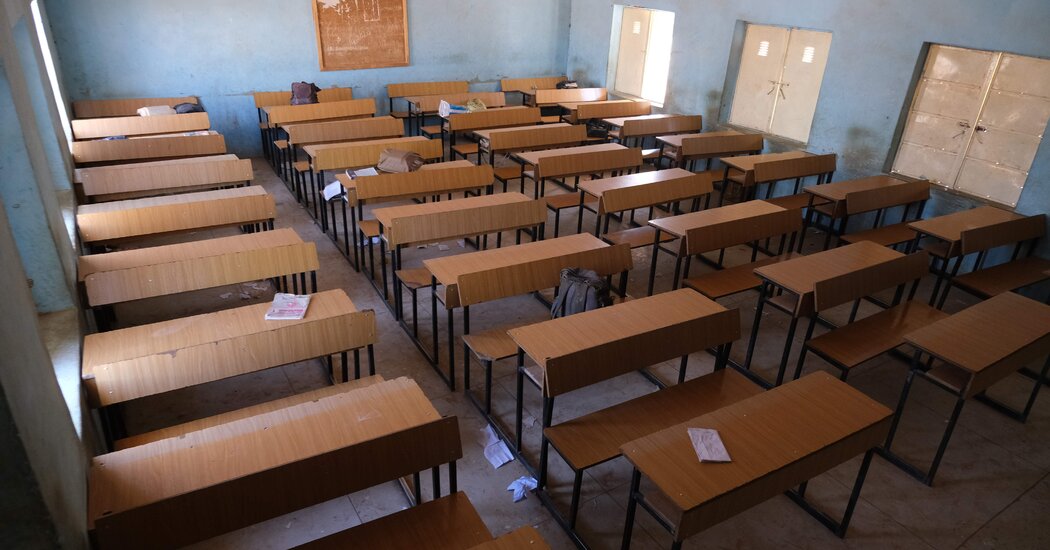

Families gathered at Government Science Secondary School, praying, and fearing the worst.

“We do not know whether he has eaten, whether he is sick, dead or alive,” said Abdulkadir Musbau, whose son Abdullahi was among the abductees.

But just as suddenly, when the families’ ordeal began, it seemed to end, and with the best possible news: late Thursday night, the governor of their state announced that all of the kidnapped boys had been released and would be reunited with their parents the next day.

It was unclear under what conditions the boys’ freedom had been secured. Governor Aminu Bello Masari told a Deutsche Welle television reporter that the government had not paid a ransom and that negotiations had been conducted with a group of men he described as “bandits” rather than Boko Haram.

Boko Haram had claimed the kidnappings from the start, but the group’s level of involvement was murky. Kankara is in northwest Nigeria, where the group was not known. Among terrorist experts, this opened up the possibility that the group might want to expand by making common cause with militant and criminal groups already established in the region.

The group seemed to confirm this idea when they posted a video showing some of the kidnapped boys. A boy who said he was from Kankara is shown asking the government to call the army, disband support groups and close schools. “We were caught by a gang from Abu Shekau,” he said, referring to the Boko Haram chief. “Some of us were killed.”

“You have to send them the money,” he added.

A dozen smaller boys crowded around him and added their voices. “Help us,” they called into the camera.

An audio message from a representative of Boko Haram was pinned to the end, implying some kind of collaboration between the kidnappers and the militant Islamists.

In a BBC interview that was taped before news of the release, Mr Masari said the kidnappers had contacted the father of one of the boys and asked the government to send them money.

“We have an idea where they are, but we try to make sure there is no collateral damage, that the children are brought back safely,” he said. “That’s why we step forward carefully and quietly.”

President Muhammadu Buhari won the 2015 election and pledged to take action against Boko Haram and other militant and bandit groups in northern Nigeria. And he has repeatedly promised to take every chibok student home.

“The Chibok girls are still fresh in our minds,” said Bulama Bukarti, an expert on extremist groups in Africa at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. “The difference now is that Boko Haram has fighters from outside the Northeast, they have people from the Northwest.”

The abductions have remarkable similarities. As in the Chibok attack, armed men stormed the boarding school at night, took hundreds of children, in this case all boys, and took them to hiding in the country. They were then divided into groups, according to students questioned by local media outlets who managed to escape their captors, making it difficult for security forces to conduct a rescue operation.

Mr Musbau said he was out shopping for pasta for his children’s Saturday breakfast when heavy gunfire broke out. People were running in all directions around him, so he sprinted home, passing police officers and guards on the way.

When he heard that their children’s boarding school was the focus of the attack, he and other parents ran there at dawn.

When he got to school, “I saw his neatly made bed and his box and hat over it,” said Mr. Musbau. “But not him.”

Mr. Musbau was delighted when Abdullahi, the oldest of his six children, got a place at the state science school. In elementary school he had reached the top of his class and was hoping to become a doctor when he got older.

“The reality became clear to us that our children were indeed abducted,” he said in a school phone interview he had barely left since the attack. “Everyone was hysterical. Nobody thought the bandits could do this. You have never done anything like this before. “

The attack in Kankara was the third mass kidnapping by a Nigerian school in six years: in 2018, more than 100 girls were kidnapped in the rural community of Dapchi, a northeastern town, although most of them returned home after a few days.

The kidnapping was significant both because it took place outside the known sphere of influence of Boko Haram and because it took place in the president’s home state, Katsina, when he arrived on a week-long visit.

Mr Buhari released a statement late Thursday evening welcoming the kidnapped students’ return and the cooperation between the security forces and the government of Katsina and Zamfara states.

In the statement, Mr. Buhari urged patience with his administration as they tried to clean up security incidents across the country and reiterated his promise to lobby for the release of other detainees.

Many northern Nigerians voted for Mr Buhari in 2015, thinking he would use his credentials as a former general and one-time dictator to encourage discipline and bring peace to Africa’s most populous nation.

Despite government claims, Boko Haram and other militant groups still pose a grave threat. And these recent attacks, following a nationwide uprising against police violence, insecurity and bad governance, have exposed the growing public dissatisfaction with a Nigerian government that cannot protect its people.

In the northeast, the government has pursued a strategy of building heavily protected garrison towns and largely leaving the land to the militants. More than 70 farmers trapped between the government and the extremists were killed there last month.

In Kankara, a local official said the government was aware of the worsening situation but had done nothing to resolve it.

“These bandits are well known, as are their families,” said the official, who asked for anonymity because he had been instructed not to speak to journalists. “Why were they treated with children’s gloves until they were monstrous and difficult to contain?”