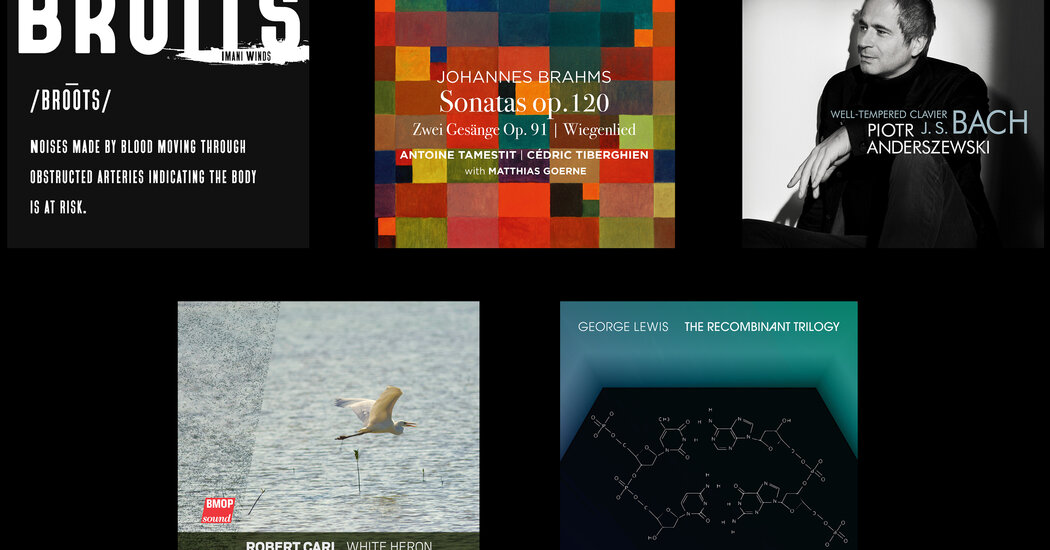

Bach: “The Well-Tempered Clavier”, Book II

Piotr Anderszewski, piano (Warner Classics)

Piotr Anderszewski is perhaps the most convincing unconventional Bach pianist since Glenn Gould, and he certainly approached his first fascinating recording of preludes and fugues from “The Well-Tempered Clavier” creatively. Not for him the typical step-by-step ascent through each of the keys from C to B minor; Instead, a jumbled selection of contrasts and additions that will raise your eyebrows but will win you over to your ears.

And how! Anderszewski’s game is a miracle of touch and temperament. When there is a chance for something unusual, something unexpected, Anderszewski takes it, as in the puckish F minor prelude or in the percussive, prickly fugue in F. Regardless of his ability to dance, he has always been a dreamer at heart, and it is also in the agony of the minor fugues that its concentrated intensity captivates and overwhelms. The one in D flat minor is reminiscent of the most deserted solitude imaginable, and a few more. the B minor somehow transforms fear into anger; The G sharp minor wanders robbed and brooding, as if it were the darkest Schumann. This is one of the great Bach recordings from that time. DAVID ALLEN

Brahms: Sonatas (op. 120), two songs (op. 91), “Lullaby”

Antoine Tamestit, viola; Cédric Tiberghien, piano; Matthias Goerne, baritone (Harmonia Mundi)

“Herbstlich” is the word most often used in connection with Brahms’ viola sonatas. These intimate, ruminating works, originally written for the clarinet, are the last chamber pieces that Brahms wrote. And there is the subdued glow of the viola’s timbre, the range of which a human voice can comfortably follow. In a duet, the sound of the viola nestles modestly into that of the piano, without the flights and lightning strikes of a violin or clarinet.

Yet there is no cozy pathos in this profound recording of Antoine Tamestit, a violist with a rare combination of stage magnetism and literal devotion to the practice of historical performance. He approaches the opening of the Sonata in E flat like a consummate dancer – sleek, elegant, and attentive. In slow movements like the dreamy Andante of the Sonata in F minor, he weaves lines of effortless charisma, equal parts light and air. Cédric Tiberghien plays a Bechstein piano from 1899 with a mother-of-pearl-colored, soft tone and is a responsive and expressive partner.

The vocal quality of Tamestit’s viola lends itself well to two arrangements of songs by Brahms: “Nachtigall” (“Nightingale”) and the famous lullaby “Wiegenlied”, which is played with sweet, wavy speed. For the last two tracks, Matthias Goerne gives the “Zwei Gesänge” (op. 91) his silky baritone, two songs in which voice and viola intertwine like lines drawn with a calligraphy brush. CORINNA da FONSECA-WOLLHEIM

“Sounds”

Imani winds (bright shiny things)

The metaphor at the heart of this new album by the Imani Winds quintet is written on the cover: “Bruits” in large, bold letters over pronunciation instructions and a definition: “Noises made by blood moving through clogged arteries and onto the Body indicates is endangered. “As a homophone, it is also reminiscent of” Brutes “- brute force, brutality.

“Bruits” takes its name from a work by Vijay Iyer, which, like Reena Esmail’s “The Light Is the Same” and Frederic Rzewski’s “Sometimes”, received its first recording on the album. Iyer wrote it in 2014 for Imani Winds and the pianist Cory Smythe and responded to the murder of Trayvon Martin with a score that smoothly spans fluid improvisation and tight complexity and leads to a climatic, uniform eruption.

Esmail’s piece – its title inspired by the observation of a Rumi poem that in a world of many religions “the lamps may be different but the light is the same” – beautifully interweaves two contrasting Hindustani ragas. One dark and the other light, their sounds flow fluently into the same room before they come together in a blissful dance.

Also in Rzewski, who plays the hopeful words of the reconstruction scholar John Hope Franklin (spoken by his son John Whittington Franklin), there are contrasts to the hopeless lines of Langston Hughes’ poem “God to Hungry Child” (sung by the soprano Janai Brugger). Between the two, the spiritual “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child” is deconstructed through a series of variations in which the theme never returns, and the end is denied a clean solution. JOSHUA BARONE

Robert Carl: ‘White Heron’

Boston Modern Orchestra Project; Gil Rose, Conductor (BMOP / Sound)

The four most recent works by Robert Carl on “White Heron” all deal with space in different ways, as the composer emphasizes in the liner notes. The title track of the album was created from Carl’s intimate observation of bird life in the Florida Keys. “Rocking Chair Serenade” for string orchestra is an elegy for “Conversation and fellowship on the veranda in the Appalachians”, inspired by memories of his youth.

The concept of space is conveyed through extended stretches of these scores unfolding in expansive, trembling, sour sounds, often arising from what Carl calls personalized harmony (a term I like) of all 12 chromatic pitches. This technique is particularly expressed in “What’s Underfoot”. Yet even in seemingly calm episodes, Carl’s music is restless beneath the surface with riffs that stimulate internal intensity and thrust.

It is gripping, almost a relief, when a piece really takes off, as in sections of Symphony No. 5, “Land”, which are bursting with frenzied energy, streams of notes and cut out eruptions. The performances under Gil Rose capture both the tonal appeal and the multilayered complexity of the music. ANTHONY TOMMASINI

George Lewis: “The Recombinant Trilogy”

Claire Chase, flute; Seth Parker Woods, cello; Dana Jessen, bassoon (New Focus)

If you are aware of the work of composer and improviser George E. Lewis, you may be wondering if you have already heard a substantial portion of his latest album, The Recombinant Trilogy, which focuses on pieces for soloists and plus electronics. (The software used for all of these works uses interactive digital delays, spatiality, and timbre conversion in response to each instrument, as noted.)

And it’s true, two of the pieces were previously released on albums by the same players who are represented here. “Emergent” appeared on the album “Density 2036: Parts I and II” by flautist Claire Chase. And “Not Alone” was part of a 2016 recording by cellist Seth Parker Woods.

That Woods recording, which was pretty definitive, is simply duplicated (although remastered) in “The Recombinant Trilogy”. But Chase took another swing here on “Emergent,” and she found a new lyrical approach to its whispering polyphony. While her earlier take was punchy and harsh – both in its electronic timbres and acoustic play – this one sounds warmer.

The premiere recording on the album – “Seismologic” for bassoonist Dana Jessen – fits the trilogy perfectly. Some of the early motifs of the piece, dark yet seductive, could have come from the Wagnerian forests. Later flights into the advanced technique bring the piece into a zone in which both the influence of Stockhausen and the brisk American jazz can be felt. SETH COLTER WALLS